Hidden History Exposed

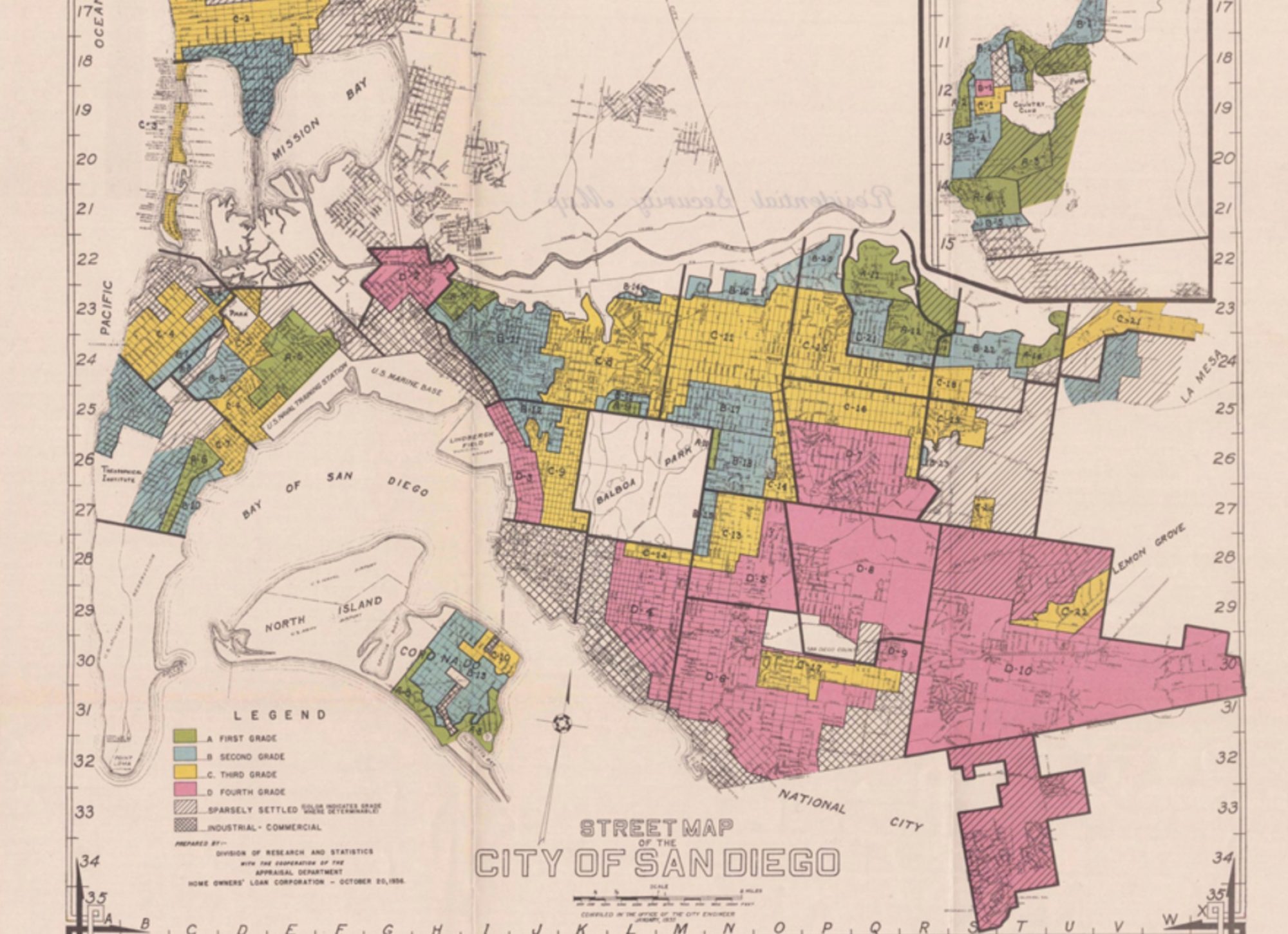

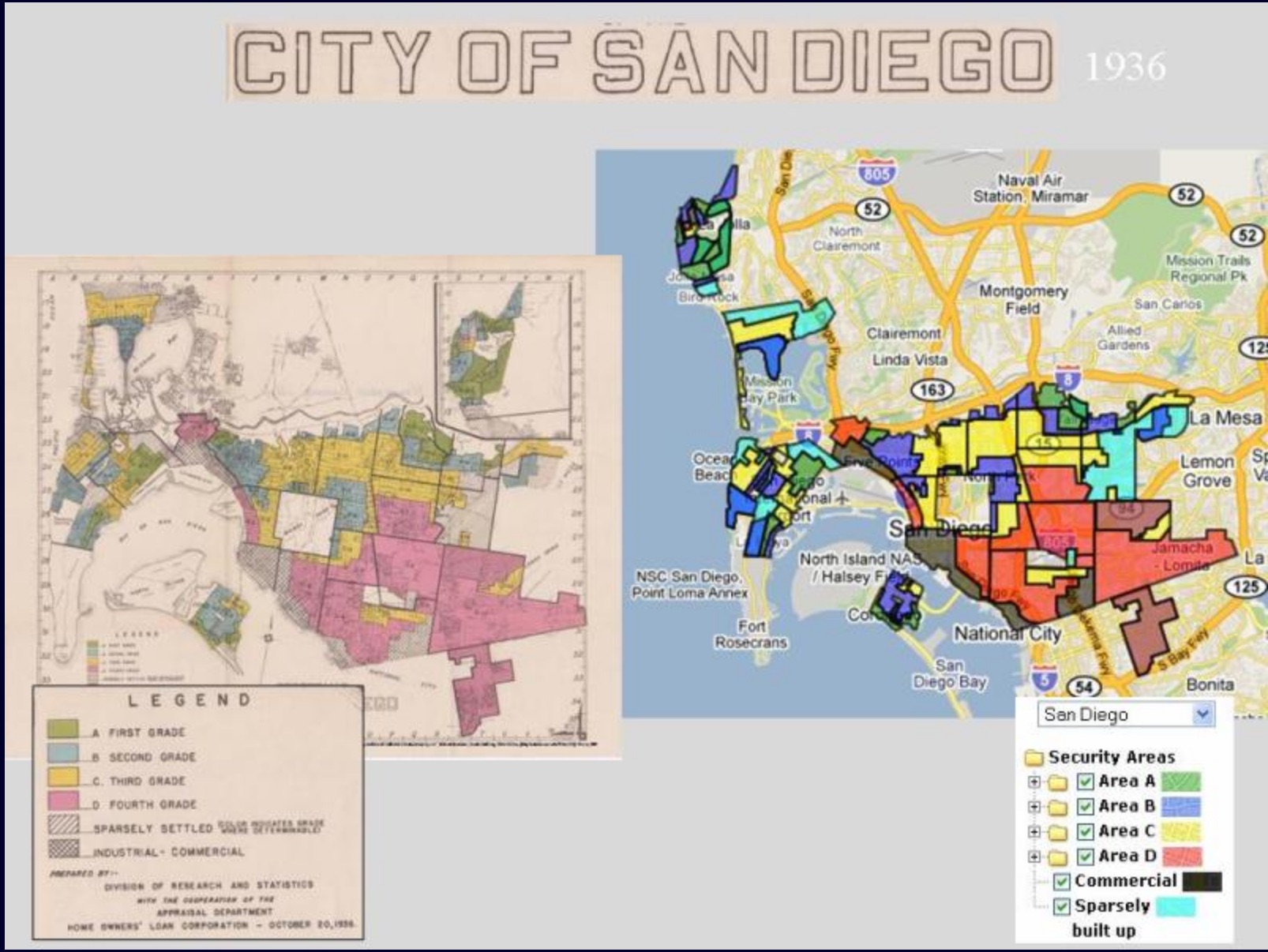

In post-World War II America, major metropolitan cities implemented discriminatory laws and regulations that helped to establish urban and suburban communities. With the creation of city maps, districts were strategically divided based on race or economic status to reflect the sociopolitical climate of the 20th century: de jure and de facto segregation. The discriminatory housing practices known as redlining became a devise tool within America’s infrastructure. For generations, the concentration of poverty and wealth illuminated for some the American Dream, and for others the American Nightmare. In order to reach the public consciousness about the immoral practices of housing discrimination, I intend to explore how the history of redlining in California becomes an instrument to conceptualize how inequality functions within American institutions. I have used primary and secondary sources such as the book, The Origins of the Urban Crisis by Thomas J. Surge, district maps, and newspaper articles to promote awareness and further discussion. Indeed, progress has been made to ensure these practices are unlawful; however, in the 21st century developers continue to find loopholes that allow housing discrimination to persists, which is often hidden from the public. With a better understanding of how housing discrimination functions in California, we can critically examine how institutions perpetuate racial and economic discrimination.

Who? What? When? Where? and Why?

Have you ever wondered why an individual’s zip code defines their reality: housing, education, jobs, entertainment, and safety? In the book, The Origins of the Urban Crisis by Thomas Sugrue, strives to answer these questions using the housing crisis in Detroit during the 1940s-1970s as a case study. Sugrue argues how post-war America provided an economic boom rooted in consumerism, yet the affluence masked significant regional variations and persistent inequality. [1]As a result, the American economy was profoundly uneven and this unevenness laid the foundation to understand how the urban crisis influenced housing discrimination in Detroit. [2] Race and economic status played a huge role in the development of suburban and urban communities in Detroit, where segregated African American and white American communities reflected the government’s overt anti-integration policy. In essence, a person’s zip code defined their access to resources, jobs, and living conditions. For African Americans in Detroit, living in the urban cities was a spatial reality.[3]

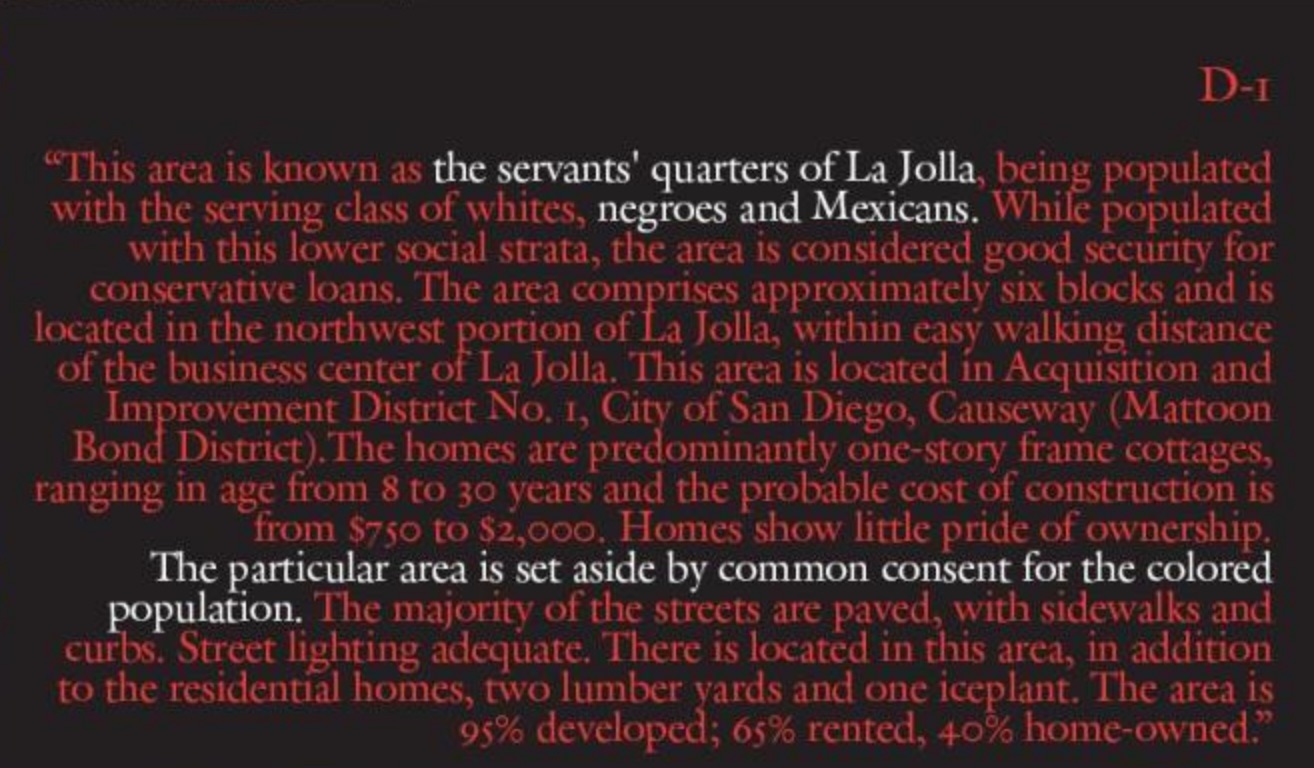

Similar to Detroit, California’s housing policies attempted to divide the black and white population. According to the article, “How Prop 14 Shaped California’s Race Covenants,” the journalist Mr. Ryan Reft discusses how the United States Supreme Court upheld the California Supreme Court’s decision to overt the controversial Proposition 14 referendum that allowed for discriminatory selling and leasing practices. Despite the implementation of Rumford Fair Housing Act of 1963 and the Fair Employee Practices Commission (FEPC), which sought to ensure homeowners or apartments did not discriminate based on race; realtors and apartments still practiced discriminatory leasing. The rhetoric of Prop 14 camouflaged the inequality. White citizens felt the policy of the Rumford Act infringed on personal liberties. In their view, the FEPC forced them to sell or lease to people of color which went against the notion of a “free market” not racism. However, statistics and maps show that even the free market projected racism. Also like Detroit, post-war housing in Los Angeles for example, had home loans that favored whites, while suburbs largely excluded Asians, Latinos and African Americans.[4] Research shows through maps and deed restrictions disproportionately supported white citizens over African American citizens in housing. The website, “In the Redlining Archives of California Exclusionary Spaces”, reinforces the arguments Reft regarding the history of overt racism in the Prop 14 laws that shaped California’s redlining practices overtime.