The Early Days of Radio Broadcasting

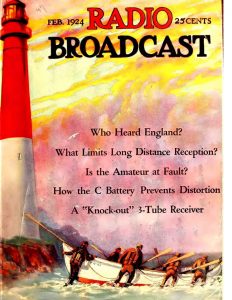

Radio broadcasting grew out of the experimentation of amateur radio operators after World War I. Many of the men who started radio broadcast stations had worked with radio in some capacity during the war.[1] According to historian Susan Douglas, most of the early radio listeners were men and boys who were willing to construct their own receivers and to spend hours trying to “reel” a signal in. In the early 1920s, amateur radio operators, who would become the first audience for broadcasting stations, surfed the “ether” to see what stations they could tune in. This practice came to be known as DXing and radio magazines and newspapers would invite readers to send in lists of stations that they received.[2] Magazines such as Radio Broadcast and Radio Digest held popular contests to see who had the highest total mileage heard from their receiver. Radio Broadcast magazine asked that the contestants share information about their receiverstating, “We are anxious to learn of experiences in broadcast reception, believing that their publication may help others to obtain the best results from their outfits.”[3] Broadcast stations in different markets had “silent nights” where they would not broadcast so the DX enthusiasts could pursue their distant stations without interference.[4]

The identity of the station that accomplished the first radio broadcast is still hotly contested. The Detroit News claims to have broadcast local election results to a small audience of amateur radio enthusiasts in August of 1920. Historian Susan Douglas proposes that the interest of amateur broadcasters in sending and receiving information led Westinghouse to support the KDKA broadcast of the election results in 1920.[5] While the KDKA broadcast was only heard locally, news of the broadcast was spread throughout the nation by amateur radio operators and soon picked up by the media.[6] The broadcast of the 1920 presidential election results over

station KDKA was the radio equivalent of the “shot heard around the world”.[7] Interest in commercial broadcasting increased dramatically over the next two years. The total number of radio broadcast licenses issued by the Department of Commerce reached a little over one hundred by the end of 1920.[8] By the end of 1922 there were about 570 radio stations in the United States.[9] Historian Christopher Sterling estimates that newspapers owned about 10% of these stations.[10]

Even though the first radio broadcast had occurred less than two years before, there was already a lively national debate about the content and control of radio in 1922. The Radio Act of 1912 specified that the Department of Commerce oversaw granting radio licenses and radio frequencies but not much else.[11] Most of the frequencies were allocated for ship to shore and government licenses; there were no provisions for the commercial land licenses that would become the broadcast stations. Until 1923 all the commercial land stations shared the same channel of 360 meters.[12] [13]In 1923, as a result of the second Washington Radio Conference, additional

bandwidths were added and stations were divided into different classes depending on the power of the broadcast station.[14] Even after four radio conferences between 1922 and 1925, Congress was not able to pass any legislation related to licensing and frequency allocation.[15] The Department of Commerce led by Herbert Hoover suffered a setback in 1926 when the Supreme Court ruled that the Department of Commerce was operating beyond of the authority granted to it in the Radio Act of 1912 and could not refuse to grant licenses or dictate the power and broadcast hours allocated to a license.[16] The anarchy created by this decision led Congress to finally act and pass the Radio Act of 1927.[17] The Radio Act of 1927 created the Federal Radio Commission (FRC), which was the precursor to the Federal Communication Commission. Congress gave the FRC the power to issue radio licenses, assign frequencies, determine the location and power of stations, classify stations, and regulate chain broadcasting. The act also prohibited the commission to censor broadcasts, especially political campaign broadcasts, except for offensive or obscene language.[18] It is important to note that while the Department of Commerce controlled the allocation of frequencies and licenses, private companies and corporations controlled broadcasting.

It is not surprising that both Los Angeles and San Diego newspapers were early adopters of radio. Due to the military and maritime industries in their cities, Los Angeles and San Diego had an active amateur radio presence before and after WWI. [19]Jack Wisemen, builder of the radio station associated with the San Diego Sun newspaper (KON), had been a military telegrapher before returning to San Diego in the early 1920s.[20] Los Angeles also was at the forefront of another new medium, the movie industry and the movie industry was already experimenting with radio on movie sets.[21] Given the higher concentration of newspaper-controlled radio stations than the national average in Los Angeles and San Diego it is surprising that so little has been written about the start of radio broadcasting by newspapers in the Los Angeles and San Diego markets.[22]

Sources for Page

[1] Erik Barnouw. Tower in Babel; a History of Broadcasting in the United States. V. 1-To 1933. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1966), 56; Susan J. Douglas. Inventing American Broadcasting, 1899-1922. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987), 298-303; Gleason L. Archer. History of Radio to 1926. (New York: Stratford Press Inc., 1938), 142-144.

[2] Douglas. Listening In, 57 – 59; Examples of these lists can be seen in the Radio Journal “Listening In” column in each issue.

[3] “How Far Have You Heard.” Radio Broadcast, November 1922, 61; “Who Hears Broadcasting Stations Farthest?” Radio Digest Illustrated. May 13, 1922, 9.

[4] “Dimmer is Placed on Air Waves” Los Angeles Times, May 6, 1923.

[5] Barnouw, Tower in Babel, 63; Douglas, Inventing American Broadcasting, 300; Archer, History of Radio to 1926, 207; “WWJ First Newspaper Plant.” Radio Digest Illustrated, April 15, 1922, 5-6; Barnouw identifies the Detroit News as the first to broadcast, Douglas and Archer identify KDKA as the first. Regardless of the controversy, the Detroit News was the first newspaper to have a broadcast station.

[6] “Radio Election News Makes Hit.” San Diego Union, Nov. 5, 1920; Department of Commerce. Radio Service Bulletin. No. 48 Washington D.C., 1921. https://apps.fcc.gov/edocs_public/attachmatch/DOC-338221A1.pdf

[7] “Concord Hymn by Ralph Waldo Emerson – 1837.” Accessed April 12, 2017.http://www.nationalcenter.org/ConcordHymn.html; For discussion of the early broadcast see

Barnouw. A Tower in Babel, 69; Department of Commerce. Radio Service Bulletin. No. 43. Washington, DC, Nov. 1920; KDKA was licensed in 1920 right before election; Asa Briggs . “Prediction and control: historical perspectives.” The Sociological Review 13, no. 1_suppl (1965): 39. Asa Briggs in his discussion of radio in Britain states that “the possibilities of broadcasting as a medium were first grasped in the United States” but only by a select few.

[8] “Radio Service Bulletins, 1915-1932,” Federal Communications Commission, last modified March 21, 2016, https://www.fcc.gov/media/radio/radio-service-bulletins; See radio service bulletins no. 34 through no. 44; The December 1920 radio service bulletin (no. 44) lists 37 radio stations receiving licenses. KDKA license was listed in the November 1920 Radio Service Bulletin (No. 43).

[9] “Radiophone Broadcasting Stations.” Radio Digest Illustrated, April 15, 1922, 10-12; “Radiophone Broadcasting Stations.” Radio Digest Illustrated, December 16, 1922, 8; “Radiophone Broadcasting Stations.” Radio Digest Illustrated, December 23, 1922, 8; “Radiophone Broadcasting Stations.” Radio Digest Illustrated, December 20, 1922, 8-9; The inaugural issue of Radio Digest Illustrated in April of 1922 lists almost 100 broadcasting stations over three pages. By the end of 1922, Radio Digest Illustrated would need to divide the list of broadcasting stations over three subsequent issues.

[10] Sterling, Christopher. “Newspaper Ownership of Broadcast Stations, 1920-68.” Journalism Quarterly 46, no 2 (1969): 228; I trust Sterling’s’ overall number at the end of 1922. He puts the number of newspaper radio owned stations at about 50. Exact numbers are hard to come by because of the volatility of station licenses as stations were added and deleted. Some of the stations that applied for licenses never broadcast or did only for a brief time.

[11] Barnouw, Tower in Babel, 31-33; Archer, History of Radio to 1926,106; Stamm, Sound Business, 45.

[12] Barnouw, Tower in Babel, 69.

[13] Barnouw, Tower in Babel, 121-122; Department of Commerce. Radio Service Bulletin. No. 74 Washington D.C., June 1,1923. https://apps.fcc.gov/edocs_public/attachmatch/DOC-338250A1.pdf; A wavelength of 360 meters corresponds to 833 kilocycles or kilohertz. The FRC identified radio station broadcast frequencies by wavelength rather than frequency until June of 1923. In Radio Service Bulletin number 74, broadcast frequencies are given in both wavelength and kilocycles. The Third Washington Radio Conference called for a reallocation of frequencies in March 1923.

[14] Benjamin, Louise. “Working It out Together: Radio Policy from Hoover to the Radio Act of 1927.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 42, no. 2 (1998): 226 – 227; “Class B Stations – New Wave-Lengths.” Radio Journal, June 1923, 344.

[15] Barnouw, Tower in Babel, 94, 121-122, 174, 177-179; Benjamin, “Working it out together”, 222 – 229; Depending on who you consult, the radio conferences are referred to as the National Radio Conferences, the Washington Radio Conferences, or just the Radio Conferences. The first conference occurred in February 1922, the second conference in March 1923; the third conference in October 1924, and the fourth conference in November 1925.

[16] Barnouw, Tower in Babel, 189; Laurence Frederick Schmeckebier. The Federal Radio Commission: Its History, Activities, and Organization. (New York: AMS Press, 1974), 12-13

[17]Barnouw, Tower in Babel, 45-55.

[18] Schmeckebier. The Federal Radio Commission, 17-18.

[19] “Amateur Radio Stations and Call Letters.” Los Angeles Times, June 25, 1922; “Veteran’s in Charge of Escondido Radio.” San Diego Evening Tribune, Nov. 5, 1920; Marie B Crane, “The Development of Commercial Radio in San Diego to 1950.” (Master’s thesis, San Diego State University, 1977), 15-21.

[20] Joe Stone. “KON Was San Diego’s First.” San Diego Union, Nov. 19, 1972.

[21] Charles F. Filstead. “Radio at the Thos. H. Ince Studios,” Radio Journal, June 1924, p. 279.

[22] Barnouw, Tower in Babel, 142; J. Fred MacDonald. Don’t Touch That Dial. (Chicago: Nelson-Hall, 1979), 3-4; Patnode. “Heralding Radio,” 25; KHJ is mentioned briefly in Barnouw; KFI and KWH are mentioned briefly in MacDonald. Patnode’s dissertation looked at the Los Angeles Times and KHJ.