The story of Japanese internment during World War II is a dark spot in recent American history. Japanese-Americans were forcibly removed from their homes to “relocation centers” or camps after President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19th, 1942. The President and others were afraid of a Japanese invasion of the West Coast coming from the Pacific and did not trust in the loyalty of Japanese-Americans. This executive order hit California hard for 120,000 Japanese-Americans were removed from the West Coast to relocation centers located throughout the country. Some centers where Japanese-Americans from the West Coast were forcibly relocated to were: Tule Lake in Northern California, Gila River on an Indian Reservation in Arizona, and Rohwer in Arkansas.

Today when we study or read about Japanese-American internment we mostly think of the effect it had on the people and families that were sent to these camps and the suffering they had to go through. Yet, the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II also had a profound impact on the local horticulture and florist businesses and economics of California. There were many Japanese-American farmers and florists who owned and operated businesses. Paul Ecke Sr. knew and worked closely with many of these Japanese-American vegetable farmers including the “Chumans the Fujimotos, the Funakis, the Furuyas, the Kosakas, the Kuroyas, the Masudas, the Nakagawas, the Nakamuras, the Nurakamis, the Sugimotos and many others.”[1]

In January of 1942, Ecke wrote to S.G. Ries Co. letting Mr. Ries know that “the S. Murata & Co., has been closed by the Federal Government because of National Japanese ownership.”[2] Ecke was inquiring if Mr. Ries knew the owners and if they were in a position to let him know if they would sell their property or what they intended to do with the building because he was sure he could find a good customer to purchase the lot. This letter shows the effect that relocation had on the local grower’s business and also that Mr. Ecke wanted to help get the property properly sold by the owners before the Government would seize the land, or before it was destroyed by those with anti-Japanese sentiment. There were many instances where those who had to leave to relocation camps had no time to secure their holdings. Houses were ransacked, some stolen off the foundation completely and others burned to the ground. Paul Sr., in 1942, did what he could to help his Japanese-American friends and fellow growers. Robert Melvin’s article states “In an unused barn, he stored machinery, furniture and personal effects for the several families who had no time to settle their affairs before being uprooted.”[3]

Businessmen and growers on the East Coast were also concerned about the effect that Japanese internment would have on business. Phillip Roland of Revere, Massachusetts contacted Ecke to ask, “will there be any change in Japanese drawing of mums and shipments east.”[4] Ecke responded that the situations on the West Coast “are in extreme turmoil”, going on to mention that “[E]ventually the production of cut flowers by the Japanese will be practically entirely eliminated…the government is giving the Japanese a limited time to dispose of their holdings and move inland, where, of course, it will be impossible for them to grow flowers.”[5] He also mentions that many of the farms would be taken over by white growers, “but there will be a definite decrease in the production of flowers here on the coast for at least a year or two…I feel that it would be well for you to figure on the basis of no ‘mams’ being shipped from here to Boston.”[6]

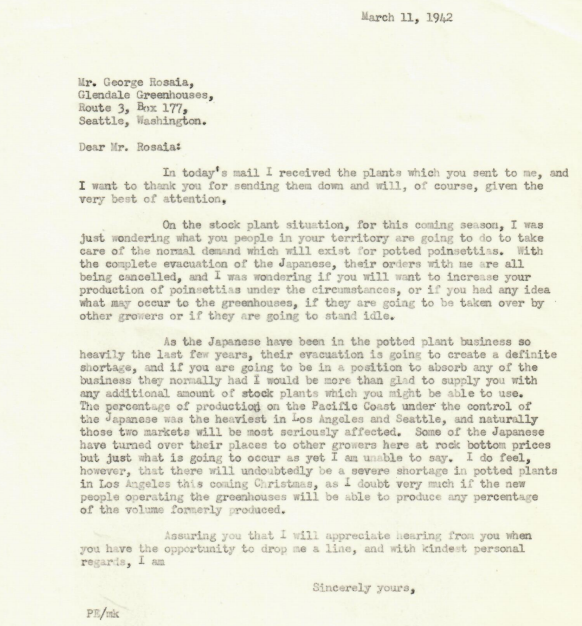

On March 11th, 1942, Ecke wrote to George Rosaia of Glendale Greenhouses in Seattle inquiring about his stock plant situation and that “[W]ith the complete evacuation of the Japanese, their orders with me are all being canceled, and I was wondering if you will want to increase your production of poinsettias under the circumstances.”[7] Ecke had a lot of business in Seattle and Los Angeles selling potted cuttings to the Japanese-American growers and now, faced with their absence, he was certain of shortages in potted plants for Christmas in Los Angeles and that “[T]he percentage of production on the Pacific Coast under the control of the Japanese was the heaviest in Los Angeles and Seattle, and naturally those two markets will be most seriously affected.”[8]

Paul supplied nurseries all over the country with poinsettia rooted cuttings so that other nurseries could sell the poinsettia during its most productive Christmas season. Yet, in 1942 many of the large Japanese-American greenhouses in the Los Angeles area were closed or being run by former employees not as skilled in growing as the Japanese owners were. In correspondence to Mission Nursery in San Gabriel, California, Paul Sr. stated in July of 1942 that “[D]ue to the fact that several of the larger Japanese greenhouses are closed such as the West Jefferson, who were among the best pot plant growers, and the fact that several of them are being operated by former Mexican employees, there is going to be a definite shortage in the Los Angeles area this Christmas of potted poinsettias.”[9]

Paul Ecke Sr. was himself a naturalized citizen, an immigrant of Germany, and couldn’t understand why Japanese-Americans were being rounded up but German-Americans were not. He did what he could for his Japanese friends by helping store their belongings, and he knew that the Japanese-American growers that were being forced to relocation centers were irreplaceable within the farming community and horticulture business of the Pacific coast.

[1] Robert Melvin, Coast Dispatch, January 25, 1989, The Paul Ecke Ranch, Inc. Business Records and Family Papers (SC001), Special Collections, California State University San Marcos Library.

[2] Paul Ecke, Sr. to S.G. Ries, January 21, 1942, The Paul Ecke Ranch, Inc. Business Records and Family Papers (SC001), Special Collections, California State University San Marcos Library.

[3] Melvin. Coast Dispatch. The Paul Ecke Ranch, Inc. Business Records and Family Papers (SC001), Special Collections, California State University San Marcos Library.

[4] Phillip Roland to Paul Ecke, Sr. Western Union Telegram, February 28, 1942. The Paul Ecke Ranch, Inc. Business Records and Family Papers (SC001), Special Collections, California State University San Marcos Library.

[5] Paul Ecke, Sr. to Phillip Roland, March 5, 1942, The Paul Ecke Ranch, Inc. Business Records and Family Papers (SC001), Special Collectios, California State Univrsity San Marcos Library

[6] Ibid.

[7] Paul Ecke, Sr. to George Rosaia, March 11, 1942, The Paul Ecke Ranch, Inc. Business Records and Family Papers (SC001), Special Collections, California State University San Marcos Library.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Paul Ecke, Sr. to Mission Nursery San Gabriel CA July 3, 1942. The Paul Ecke Ranch, Inc. Business Records and Family Papers (SC001), Special Collections, California State University San Marcos Library.